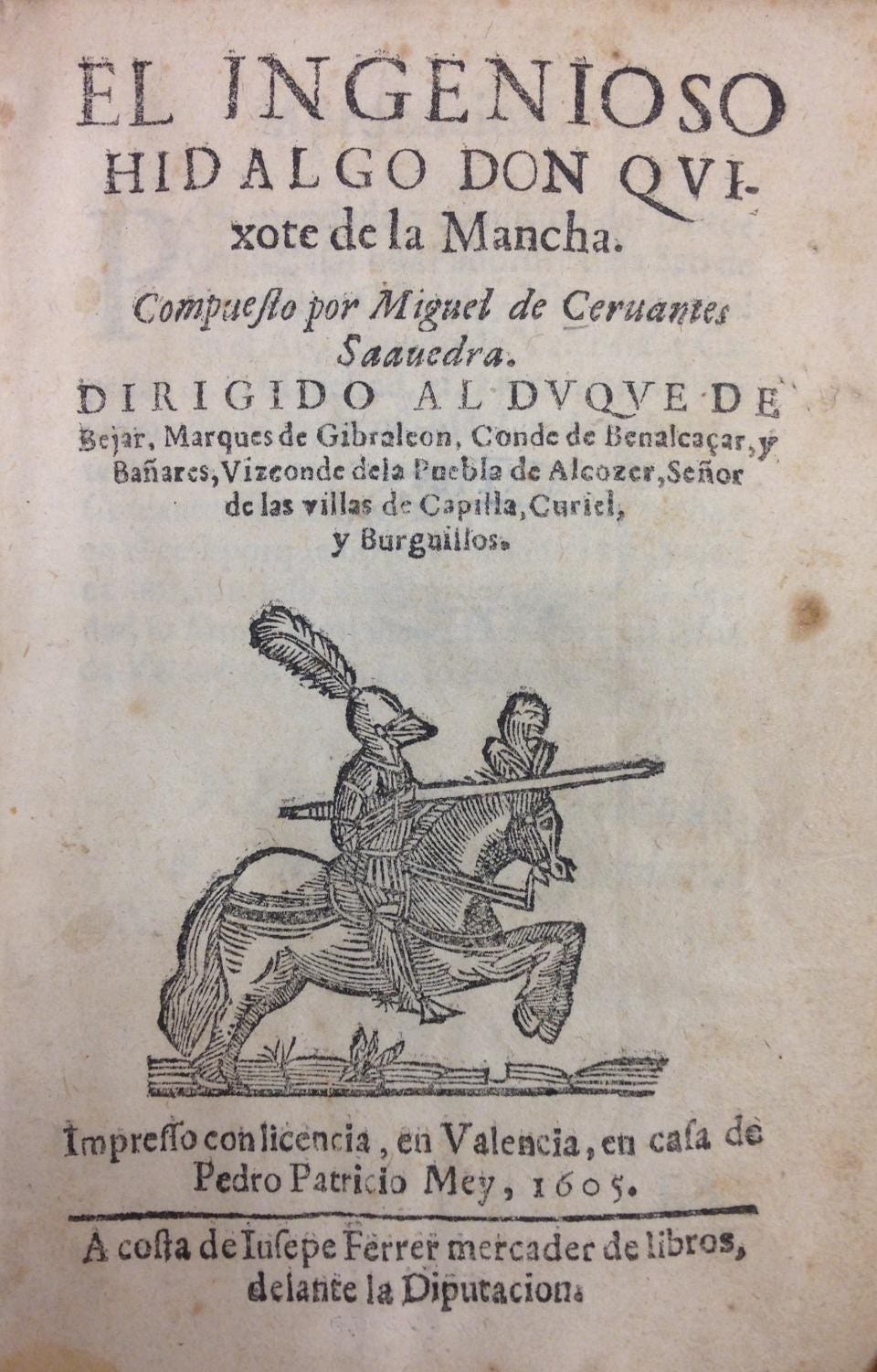

El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (better known simply as Don Quixote) by Miguel de Cervantes is the beloved classic about a middle-aged man so obsessed with tales of chivalry that he loses his mind and imagines himself to be a knight errant in quest of adventure–or misadventure.

Don Quixote is widely considered to be one of–if not the first–modern novels. Despite being over four centuries old, comprising over 1,000 pages in most editions, and being translated from Spanish, the book is surprisingly readable in English and manages to produce a protagonist readers can both laugh at and feel great sympathy and affection for.

The word “quixotic” (adj: exceedingly idealistic; unrealistic and impractical) as well as the expression “tilting at windmills”–which means fighting nonexistent foes–are both derived from Don Quixote (readers are slow to forget the scene where Don Quixote jousts with windmills he’s hallucinating as giants). I haven’t read the book in over a decade but Don Quixote mistaking the barber’s shaving basin as a knight’s helmet, his “noble steed” Rocinante, his down-to-earth “squire” Sancho Panza, and his undying devotion for his lady-love Aldonza Lorenzo (whom he fantasizes as the princess Dulcinea del Toboso) remains as indelible as ever.

What many readers forget–myself included–is how the book ends. (If you’re hoping to avoid any spoilers, avert your eyes.)

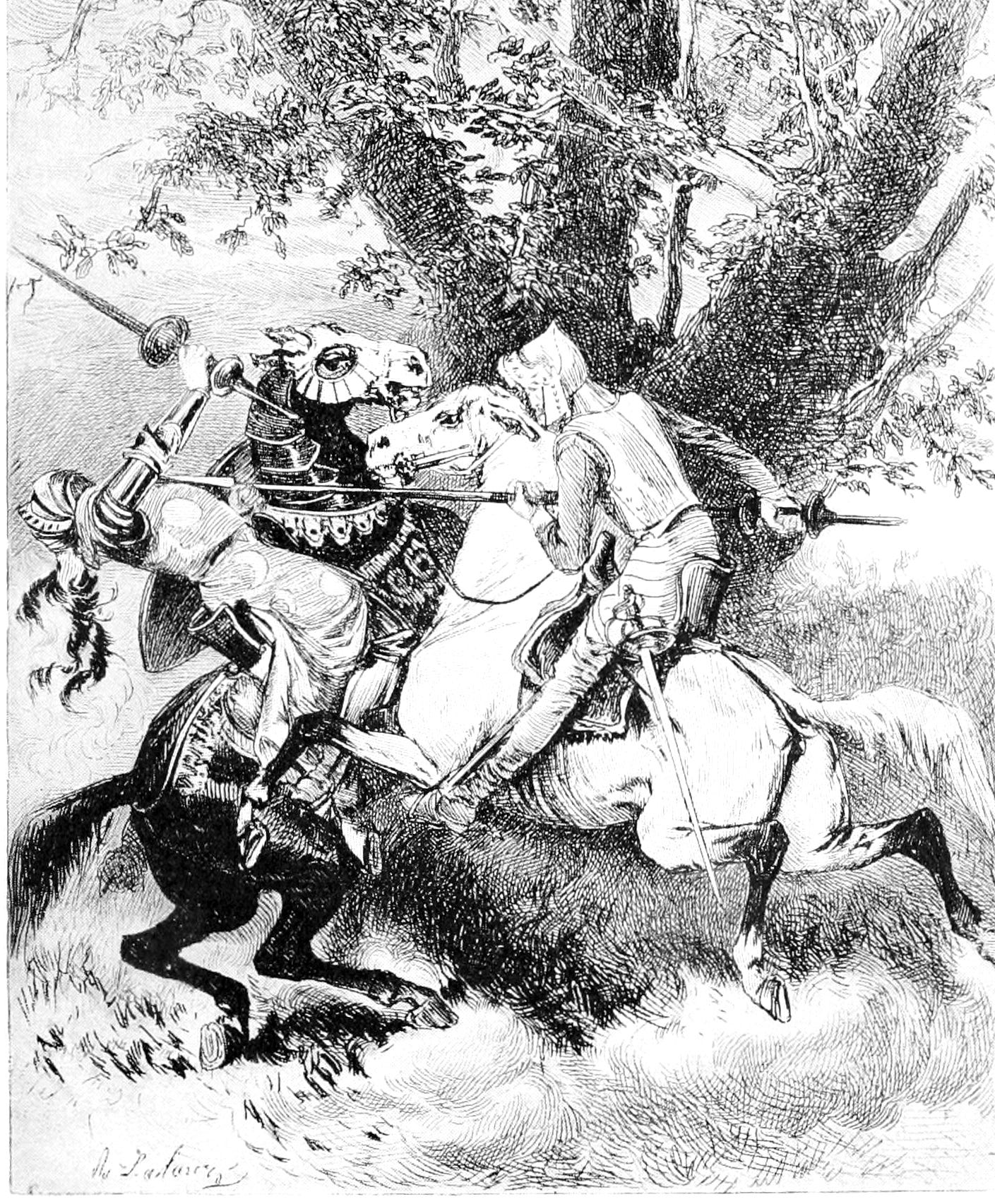

In a nutshell, it goes like this: after a series of misadventures, Don Quixote is confronted by an armored man on horseback claiming to be the “Knight of the White Moon” who provokes him into a fight by besmirching Quixote’s love-interest Dulcinea. This “knight” is, in fact, Carrasco, a man from Quixote’s hometown bent on tricking Quixote into laying down his arms and abandoning his delusions of grandeur.

After reading about 1,000 pages of wacky hi-jinks and silliness, we expect the climax of the book to be something spectacular, albeit ridiculous. Instead we get:

And then, without blare of trumpet or other warlike instrument to give them the signal for the attack, both at the same instant wheeled their steeds about and returned for the charge. Being mounted upon the swifter horse, the Knight of the White Moon met Don Quixote two-thirds of the way and with such tremendous force that, without touching his opponent with his lance (which, it seemed, he deliberately held aloft) he brought both Rocinante and his rider to the ground in an exceedingly perilous fall. At once the victor leaped down and placed his lance at Don Quixote’s visor.

You are vanquished, O knight! Nay, more, you are dead unless you make confession in accordance with the conditions governing our encounter.

Don Quixote, defeated, returns home, where he promises to remain for a year. During this time, Don Quixote falls ill, renounces the books of chivalry which deluded him into believing he was a knight, and dies.

The End.

Exit Don Quixote de La Mancha.

Enter Vladimir Nabokov del Harvard.

Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita fame was also a professor of literature, first at Wellesley College, then Cornell, and finally Harvard as a visiting lecturer in 1952. (He continued to teach at Cornell until 1959.)

Although he specialized in Russian literature (no surprise there), Nabokov gave extensive lectures on many other books, including Don Quixote. What may surprise some readers is to learn that, at first, Nabokov didn’t think too highly of Cervantes’s magnum opus.

According to the foreword of Lectures on Don Quixote:

“I remember with delight,” Vladimir Nabokov said in 1966 to Herbert Gold, who had traveled to Montreux to interview him, “tearing apart Don Quixote, a cruel and crude old book, before six hundred students in Memorial Hall, much to the horror and embarrassment of some of my more conservative colleagues.”

Not only did Nabokov consider the book to be “cruel and crude”, he didn’t find it funny at all. Nabokov writes:

Even if allowance be made for the fading away of the Spanish in the twilight of translation, even so Sancho’s cracks and proverbs are not very mirth provoking either in themselves or in their repetitious accumulation. The corniest modern gag is funnier.

In the end, however, Nabokov was pressured enough into teaching Don Quixote that he gave the book a close re-reading and gradually had a change of heart.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Nabokov didn’t read Don Quixote as an epic farce full of slapstick comedy. Instead he saw the book as a fictionalized account of human cruelty against the mentally unwell. Our hero Quixote was less a rodeo clown and more of an exemplar of justice and righteousness in an age not known for its humanism and compassion.

Nabokov had become something of a fan, although the critic in him remained:

Don Quixote has been called the greatest novel ever written. This, of course, is nonsense. As a matter of fact, it is not even one of the greatest novels of the world, but its hero, whose personality is a stroke of genius on the part of Cervantes, looms so wonderfully above the skyline of literature, a gaunt giant on a lean nag, that the book lives and will live through the sheer vitality that Cervantes has injected into the main character of a very patchy haphazard tale, which is saved from falling apart only by its creator’s wonderful artistic intuition that has his Don Quixote go into action at the right moments of the story.

One of the features of Nabokov’s Lectures on Don Quixote is a lengthy section wherein Nabokov summarizes the action of each chapter of the book while providing insights and commentary. This is especially valuable because although there isn’t much to Don Quixote in terms of plot, there is a story behind the story that transforms the novel into something greater than the sum of its parts.

Not only is Don Quixote an early example of the picaresque novel, it’s also a work of metafiction. The narrator of the story isn’t the author, Miguel de Cervantes, nor is it Don Quixote himself. Instead, the narrative (as the story goes) is a translation from Arabic by the (fictional) Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli. Framing the story this way allows Cervantes to lend some credence to the exploits of Don Quixote, as if he were an actual figure of Spanish history.

In addition, although often thought of as one book, Don Quixote was originally published as two separate parts–in 1905 and 1915. This means that, within the universe that Cervantes constructed, the characters in the second half of the story were aware of who Don Quixote was and had read about him from Part 1.

Now this is where things get interesting.

In 1614, an author (or group of authors) using the non de plume Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda published an unauthorized sequel to the first Don Quixote book called the Second Book of the Ingenious Knight Don Quixote of La Mancha. It should be noted that there were no copyright laws in the early 17th century. (The first modern copyright laws wouldn’t exist until 1709–a full century later.)

It remains unclear whether or not Cervantes was already at work on the real Part 2 when the unauthorized version was published. In any case, the following year Cervantes published his Don Quixote sequel and managed to deal with Avellaneda in his own metafictional way.

Throughout Part 2, Don Quixote meets characters who are aware of him from his misadventures in Part 1. However, he also meets characters who featured in Avellaneda’s version. In one scene, Don Quixote refuses to attend a jousting tournament because the same tournament was part of Avellaneda’s “false” story.

In yet another scene, Don Quixote visits a printing house that’s publishing Avellaneda’s Part 2 and spears one of the copies.

Later, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza meet Don Alvaro Tarfe–an Avellaneda character–and have him sign an affidavit swearing that the “other” Don Quixote and Panza are impostors.

But perhaps the most damning scene comes near the end of the book. In chapter 70 the character Altisidora tells a story about her journey to hell, where she witnessed a group of devils playing tennis with books instead of balls. She recounts:

To one of them, a brand-new, well-bound one, they gave such a stroke that they knocked the guts out of it and scattered the leaves about. “Look what book that is,” said one devil to another, and the other replied, “It is ‘Second Part of the History of Don Quixote of La Mancha,’ not by Cid Hamet [the metafictional historian of Don Quixote], the original author, but by an Aragonese who by his own account is of Tordesillas.” “Out of this with it,” said the first, “and into the depths of hell with it out of my sight.” “Is it so bad?” said the other. “So bad is it,” said the first, “that if I had set myself deliberately to make a worse, I could not have done it.”

Needless to say, Cervantes used his quill like a sword.

But for all his literary wit, Nabokov felt that Cervantes dropped the ball and squandered an opportunity to land a slam dunk on Avellaneda. The actual ending of Don Quixote felt to Nabokov (and to me) abrupt and somewhat sloppy, as if what Cervantes wanted more than anything was to close the book on Don Quixote for good so that no more frauds and plagiarists could hijack his knight for their own gain.

In Nabokov’s Lectures on Don Quixote, he writes an alternate ending to the final fight scene that puts Cervantes’s version to shame:

It seems to me that the chance Cervantes missed was to have followed up the hint he had dropped himself and to have Don Quixote meet in battle, in a final scene, not Carrasco but the fake Don Quixote of Avellaneda. All along we have been meeting people who were personally acquainted with the false Don Quixote. We are as ready for the appearance of the fake Don Quixote as we are of Dulcinea. We are eager for Avellaneda to produce his man. How splendid it would have been if instead of that hasty and vague last encounter with the disguised Carrasco, who tumbles our knight in a jiffy, the real Don Quixote had fought his crucial battle with the false Don Quixote! In that imagined battle who would have been the victor--the fantastic lovable madman of genius, or the fraud, the symbol of robust mediocrity? My money is on Avellaneda's man, because the beauty of it is that, in life, mediocrity is more fortunate than genius. In life it is the fraud that unhorses true valor.

What an incredible ending that would have been. The level of metafiction at play was so sublime, it seems impossible that Cervantes could have missed a more perfect set up. Perhaps his ego got in the way–his hate for Avellaneda is palpable all these centuries later–and he refused to allow the false Quixote to ride triumphant over the real Quixote.

At the risk of quoting too greatly at length, here is Nabokov’s parting remarks on the mad gallantry of Cervantes’s knight errant:

We are confronted by an interesting phenomenon: a literary hero losing gradually contact with the book that bore him; leaving his fatherland, leaving his creator’s desk and roaming space after roaming Spain. In result, Don Quixote is greater today than he was in Cervantes’s womb. He has ridden for three hundred and fifty years through the jungles and tundras of human thought–and he has gained in vitality and stature. We do not laugh at him any longer. His blazon is pity, his banner is beauty. He stands for everything that is gentle, forlorn, pure, unselfish, and gallant. The parody has become the paragon.

(Purchases made through affiliate links earn this newsletter a small commission)

Really enjoyed this - very well researched. I never quite finished Don Quixote - it was one of the many books offloaded in my Tongyeong fire sale. Had no idea about the metanarrative. Wild.