Su Hui’s Epic Palindrome: Star Gauge

The 4th century Chinese poem that can be read in every direction

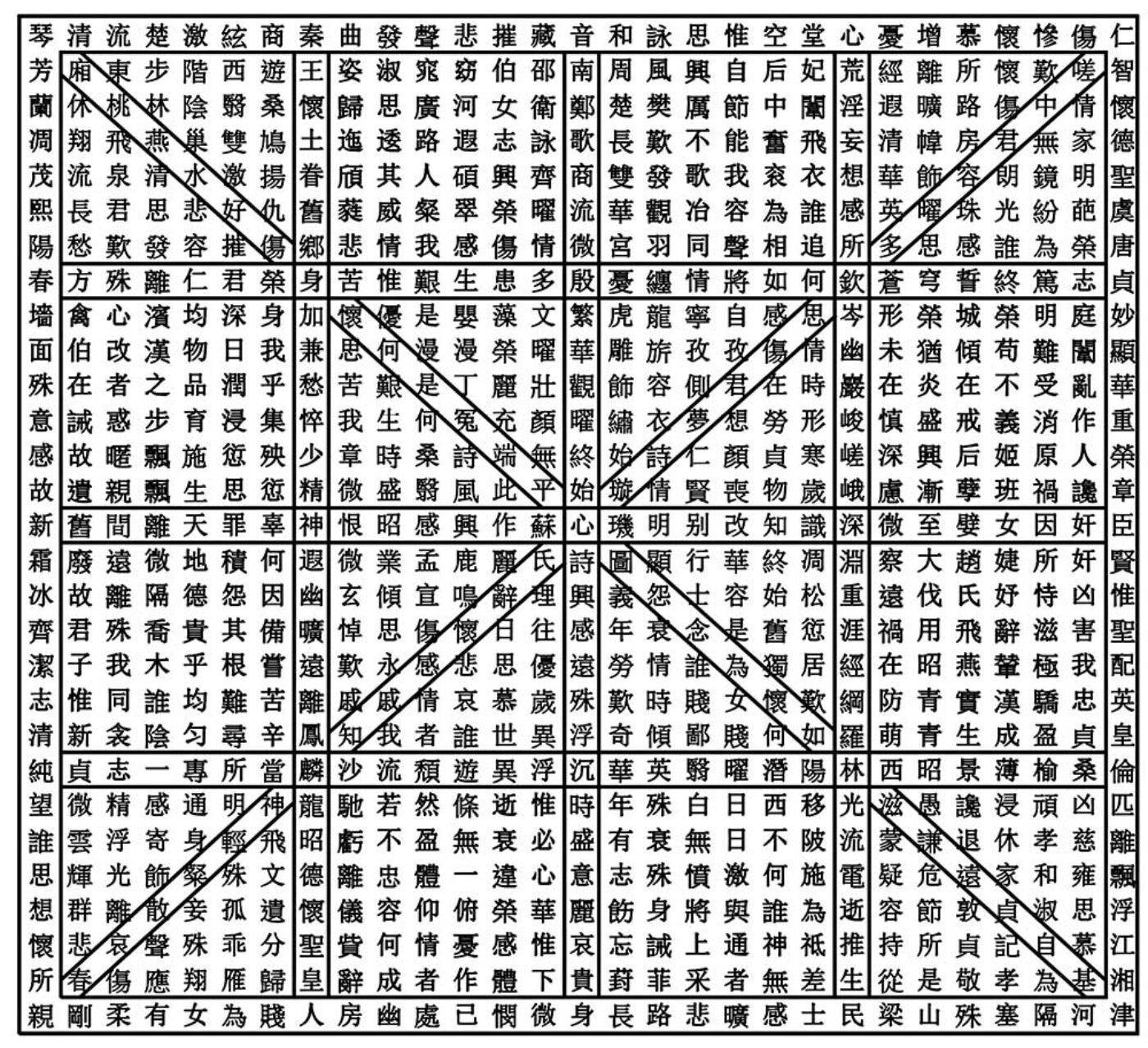

The “Star Gauge”, also known as Xuanji Tu (璇玑图); or, “The Map of the Armillary Sphere” is a 4th century Chinese poem by Lady Su Hui written sometime during the Sixteen Kingdoms (AD 304 to 439) period of Chinese history.

Su Hui, who was famous in her time for palindrome poems woven on brocade, is best known for “Star Gauge”, an 841-character grid that can be read in any direction (including diagonally) both forward and backwards, as well as within the gridded areas comprising the poem. The outermost characters are meant to be read in a circle—clockwise or counterclockwise will yield different results. At the center is the single character 心, which translates to “heart/mind”.

There are some who believe the poem can be read in as many as 12,000 ways. It has even been suggested, considering how Chinese characters can act as any part of speech and can have dozens of different meanings, that the number of smaller poems contained within “Star Gauge” is infinite.

Oh, yeah, one more thing—it also rhymes.

A Brief Origin Story

As is the case with many stories from over 1,500 years ago, the origin of the poem is steeped in legend, so we’ll never know for sure exactly where fact and fiction intertwine.

In a nutshell, the story goes something like this:

The Lady Su Hui married government official Dou Tao of Qinzhou at the age of 15 and they lived happily together. One day her husband took in a concubine (considered normal at the time) which enraged Su Hui. When he was transferred to a distant post, she refused to go with him. Dou Tao took off with his new lover and left Su Hui behind. Brokenhearted, Su Hui composed “Star Gauge” and had it sent to her husband to win him back. According to legend, when he read the poem, Dou dropped his concubine like a sack of potatoes and immediately returned home to Su Hui.1

Unfortunately, much of what we know about Su Hui has been tainted over the centuries. According to the abstract of an article by Qiaomei Tang in NAN NÜ journal:

…Su Hui is remembered today primarily as a talented but jealous wife, which is in contrast with how she was viewed in the period prior to the Wu version. In ‘boudoir lament’ poetry of the Southern Dynasties period, Su Hui is the stock image of a melancholy wife longing for her absent husband. In ‘frontier’ poetry of the Tang dynasty, she is a worrying wife concerned with her military husband fighting on the borderlands. It is in a Late Tang prose account misattributed to [empress] Wu Zetian that we finally see her as a jealous woman competing for her husband’s affections.2

Whatever the truth may be regarding Su Hui’s character, her genius is undeniable.

How to Read “Star Gauge”

(I’ve linked an interactive version of the poem that lets you read some translations of the characters if you hover over them with your cursor here.)

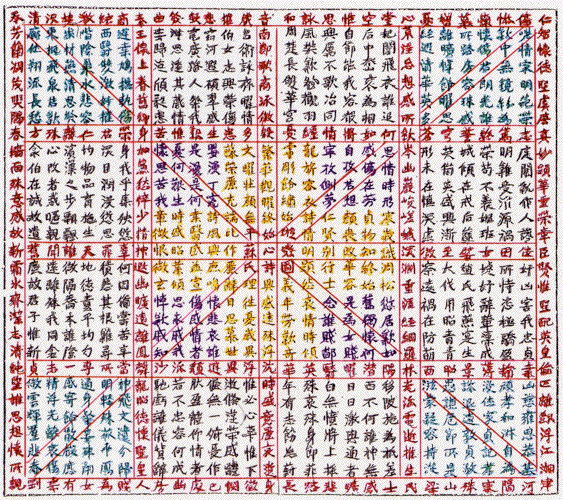

Su Hui’s version of the poem was color-coded to guide the reader. The original may have looked something like this:

Let’s start with the red characters that form the grid pattern of the poem.

The red-colored segments can be read starting at any location, as long as at the end of each 7-character segment you arrive at a juncture of meridians wherein you choose which direction you want the poem to go next. Each 7-character segment forms one line in a quatrian (4-line poem or stanza), until you’ve read four lines, thus creating your own poem. (2848 poems can be discovered this way.)

The colored sections have different patterns. The top right corner (in blue) is made up of 3-character lines that form 6- or 12-lined poems, for example. The only “rule” or contraint that remains the same in each section of the poem is this: the second line of every couplet must rhyme.

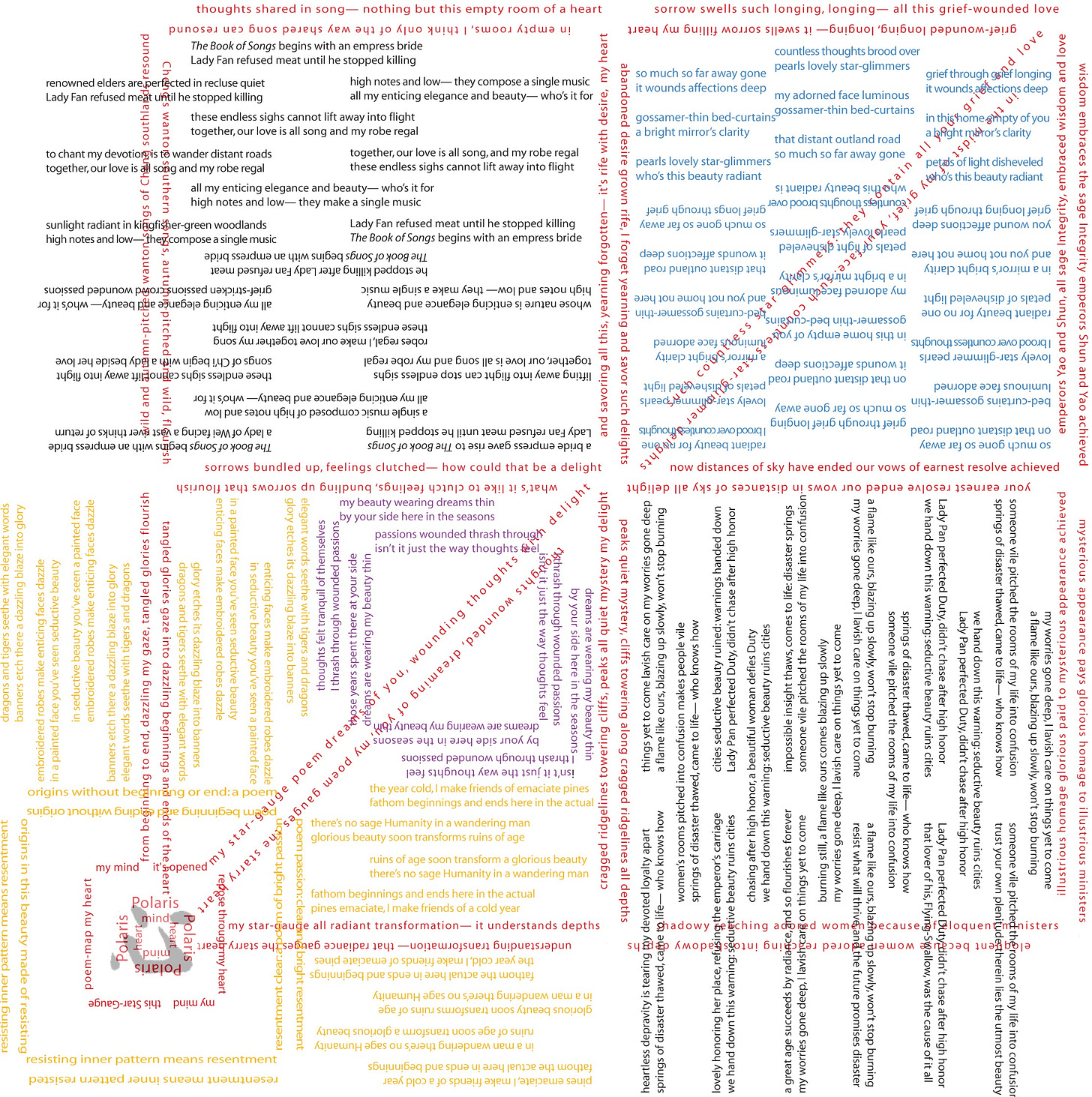

It would take an entire book to unravel even a fraction of the translations of the mini-poems contained within the larger work, but here is a visualization of a partial translation by translator David Hinton:

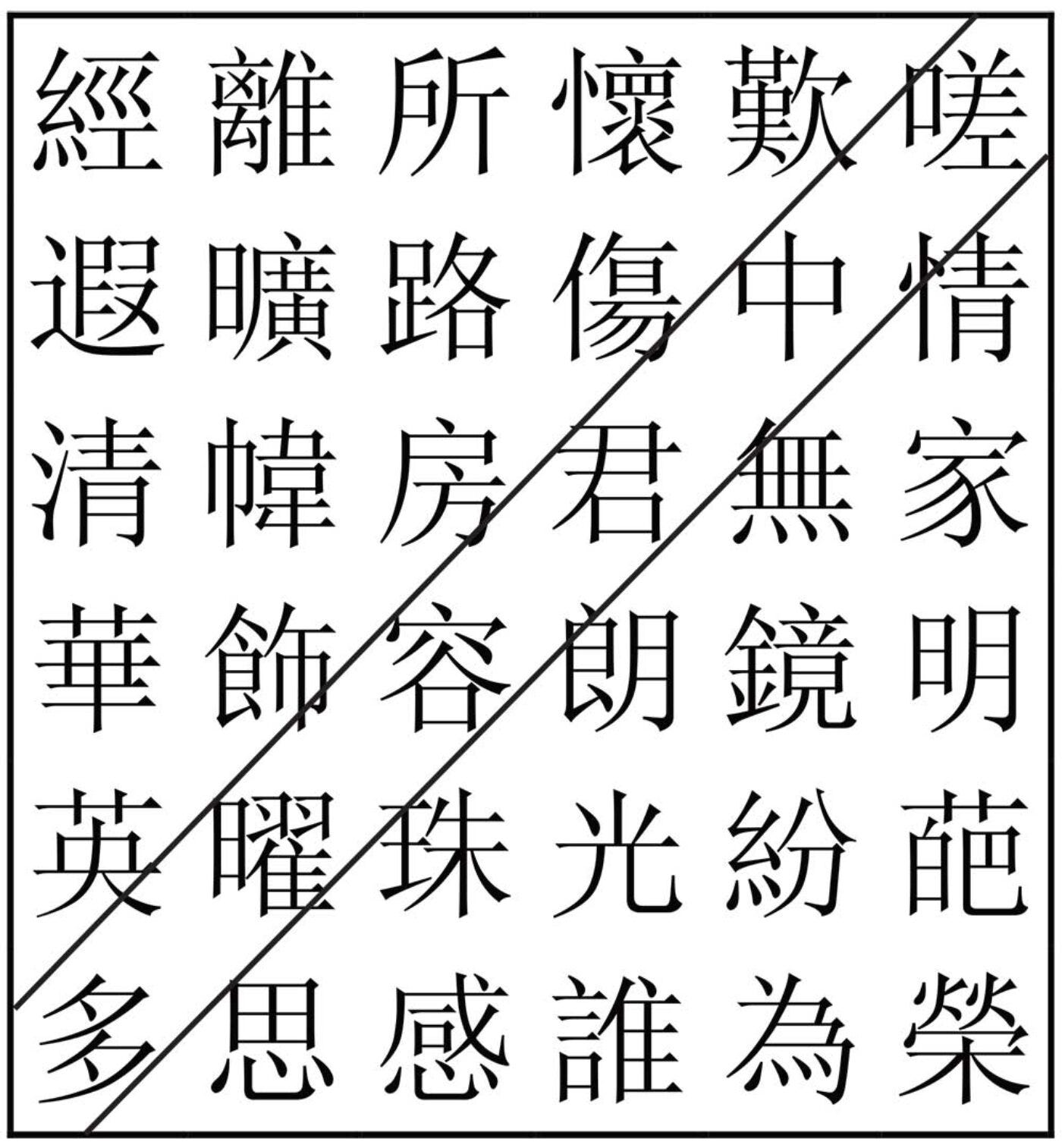

Here is a close-up of the top-right section of the poem, followed by two translations by Jody Gladding:

According to the first way of reading:

Alas! I sigh with languor

Over the one who wandered from the way.

Far-off the wilderness path

Wounded my innermost feelings.

The house no longer has a master

Transparent curtains in the alcove.

The face equally adorned

In the bright mirror shines forth.

Ornaments of the multiple reflections

The pearls gleam, brilliant.

So many thoughts assail me

Who is seen honored there?Second way of reading, reverse of the one above:

To whom does the honor revert

For prompting so many thoughts?

Brilliant, the splendor of the pearls

Reflections of multiple ornaments.

Luminous the mirror shines

Elegant finery of the face.

Room with transparent curtains

You no longer have a home.

Feeling of a deep wound

The path disappears into the wilderness.

The way withdraws from here

Me languishing, I sigh, alas!The two lines "The house no longer has a master" and "You no longer have a home" give some idea of the change in meaning introduced by the reverse reading.3

There are many more ways to read just that one section of the larger work, but, again, it would take a much longer post than this just to scratch the surface.

Michèle Métail, editor of Wild Geese Returning: Chinese Reversible Poems writes, "The important thing is not so much the exact number of poems, nor how exhaustively we read them, as it is the vertigo that grips the reader facing the open work, facing the infinitely unfurling meaning."4

What do you think about Su Hui’s incredible “Star Gauge”? Let me know in the comments.

Hinton, D. (2012, February). Su Hui’s Star Gauge – David Hinton: Poetry of China. Su Hui’s Star Gauge – David Hinton | poetry of China. https://poetrychina.net/welling-magazine/suhui

Tang, Q. (2020). From Talented Poet to Jealous Wife: Reimagining Su Hui in Late Tang Literary Culture. NAN NÜ, 22(1), 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685268-00221P01

Xuanjitu. BOMB Magazine. (2017, March 15). https://bombmagazine.org/articles/xuanjitu/

Métail, M., Gladding, J., & Yang, J. (2017). Wild geese returning: Chinese reversible poems. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

I remember when I first encountered “Star Gauge” ((璇玑图) in a Chinese Literature class in college. It blew my mind, but seemed incomprehensible. I loved your breakdown of Su Hui's (蘇蕙) masterpiece.

Fascinating and well-researched. Poetry probably deserves more of my attention. Where to start?